Highly Vulnerable Children’s Research Center makes significant progress on HIV in South Africa

South Africa has the highest rate of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the world, leaving children vulnerable to becoming orphaned or at risk for poverty and illness.

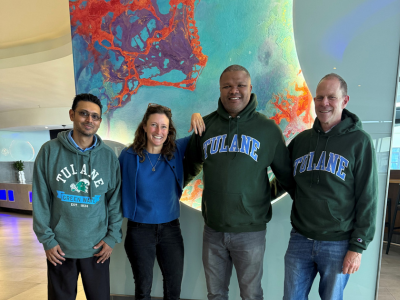

Since 2010, the Highly Vulnerable Children’s (HVC) Research Center in South Africa has been the lead research institution working with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Southern Africa to ensure best practices for children and families affected by HIV. The center was launched by the Tulane University School of Social Work, but it became part of Tulane’s Celia Scott Weatherhead School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine’s portfolio when Associate Professor Dr. Tonya Thurman joined the Department of International Health & Sustainable Development.

Over the past 15 years, the center has developed a standardized system to monitor program processes leading to routine collection of high-quality data across USAID-funded implementing partners in the country. Building on that data, Thurman and her colleagues have established interventions and conducted evaluations designed to improve child wellbeing and build country capacity to address the needs of the most vulnerable children.

The HVC Research Center has contributed to numerous successful projects. As part of the research in South Africa, randomized control trials and quasi-experimental studies identified effective interventions that could be scaled to reduce sexual risk behaviors and improve mental and physical health outcomes.

Significantly, the center designed and managed a secure, web-based database—Community-Based Information Management System (CBIMS.Net)—to streamline monitoring and reporting across USAID-funded PEPFAR programs in South Africa. With CBIMS, the center has provided vital case management data to help partners track and enhance delivery of HIV-related services. As of February 2025, the center has tracked the following data pointing to their success:

- 20 million+ services delivered

- 2.4 million adolescent girls and young women receiving layered HIV prevention interventions

- 830,000 children and caregivers receiving comprehensive case management

- 197,000 young adolescents reached through HIV and sexual violence prevention interventions

- 140 nonprofit and community-based partner organizations involved

HVC staff have also been effective at program development, including the creation of an evidence-informed family-strengthening intervention for HIV prevention called Let’s Talk. They collaborated with South Africa’s Department of Social Development to support wide-scale adoption of this and other evidence-based curriculum. The center’s free online courses for program implementers also helped build capacity and strengthen workforce readiness.

Dr. Johanna Nice, IHSD assistant professor and deputy director for the project, highlighted the importance of the center’s success, which was started as an emergency response.

“They basically lost a generation of parents -- people who weren't receiving treatment and so passed away from AIDS and also passed it on to children,” she said. “So, you had a large number of children born with HIV and a large number of children who had lost one or both parents.”

Assisting those individuals was of primary importance, but also learning how to support them as effectively as possible was a critical part of the mission. Those insights can be applied throughout the world, including in the United States.

“Since we've been doing this, we've seen this massive shift from treating it as an emergency response to this very planned, well-managed response that was evidence-based,” Nice said.

That research and data provided high-quality data for decision-making to support the implementing partners on the ground who provide support services and care to families affected by HIV.

“We’ve seen fewer people dying from HIV-related deaths, fewer babies born with HIV, and community-based programming that was developed to ensure that children could stay in their communities and with extended families and weren't institutionalized,” said Nice.

Best practice approaches are most effectively developed through research that is grounded in the lived experiences of those most affected. Research within South Africa, the epicenter of the HIV epidemic, lends critical lessons to inform public health policy and practice globally.

And as home to roughly a quarter of the world’s population, the continent of Africa has a significant impact on the rest of the world.

“Diseases don’t care about borders,” says Thurman. Efforts to address epidemics in Africa, she says, contribute to safeguarding global health, including the health of Americans.

An interruption in federal funding for the center has already led to a gap in study. The loss of funding for the Tulane-led center is coupled with the broader termination of NIH and other federal funding for HIV and AIDS research globally. Maintaining access to government websites ensures that critical findings continue to inform medical and public health practices.

“We have lost opportunities for advanced science and informed practice,” Thurman said. “Government-supported research in Africa has contributed to groundbreaking findings for HIV care and prevention, such as new HIV formulations, prevention medicines and models of care applicable to American people.”

A recent Lancet article reports that PEPFAR (the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) has saved over 26 million lives globally. In contrast, a total stoppage of these programs – now in play due to USAID cuts – would result in an estimated additional 13 million AIDS-related deaths by 2030.

“PEPFAR’s help of vulnerable people also builds goodwill towards America, thereby improving national security, increasing trade, and strengthening our scientific leadership and capacity to respond to epidemics,” Thurman adds.