Health justice remains elusive 50 years after Tuskegee Syphilis Study

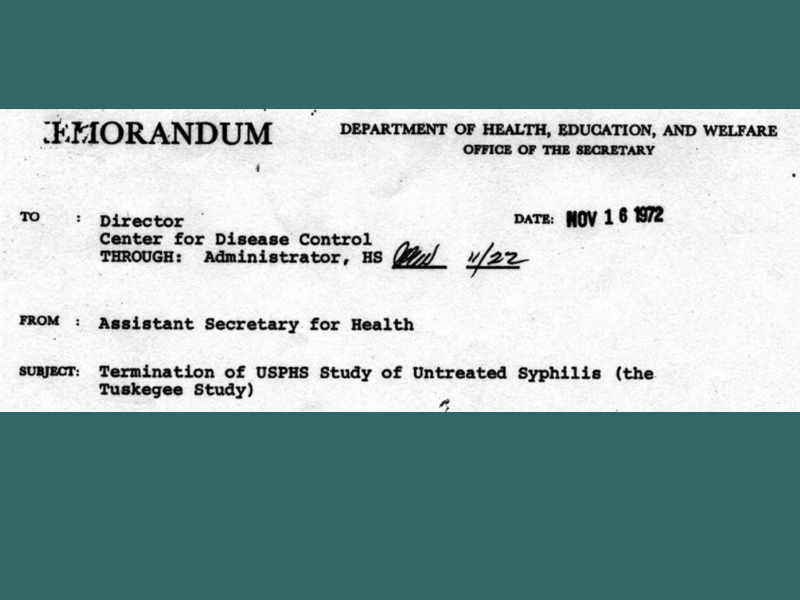

November 16, 2022 marked the 50th anniversary of the termination of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the most notorious public health ethics violation in U.S. history. The study was started by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) with the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in 1932.1 They sought to document the untreated course of syphilis among Black/African American men; 600 poor sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama–399 with latent syphilis, and 201 without syphilis were the study subjects. The men with syphilis were not told they had the disease, nor were they treated, despite the advent and subsequent widespread availability of penicillin, which became the standard treatment in 1947. The study ended in 1972 only after a PHS investigator notified the press and the ensuing public outrage. By then, 128 of the men died from the disease or its complications, 40 wives contracted the disease, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.(1)

Exposing the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (officially the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male) led to a seismic shift in how human research is conducted in the U.S.; it led to the Belmont Report, creation of the Office of Human Research Protections, and laws and policies regarding the treatment of research participants, including institutional review board approvals.(1) These measures have led to greater assurance that human research is conducted in an ethical and just manner. However, health justice for the residents of Macon County remains elusive.

Predominantly Black/African American rural counties in the U.S., including Macon County, are grossly overlooked, despite facing some of the most significant health inequities.(2) Black/African American rural communities are characterized by concentrated systemic and structural disadvantage and segregated poverty.(2) Almost half of Black/African Americans living in rural areas reside in high-poverty counties, compared to 10% of rural Whites.(3) Rural areas in the U.S. South with higher percentages of Black/African Americans tend to have lower wage and poorer quality jobs.(4) In addition to being more likely to live in physically substandard housing, rural Black/African Americans are exposed to higher concentrations of physical toxins; they are more likely to live in areas with deficits in the service environment, such as food deserts and swamps, have less access to parks and recreational outlets, and have fewer health care facilities.(4)

According to 2020 data, 80% of Macon County is Black/African American, while only 16% is White; 40% of children are living in poverty.(5) Compare these figures to neighboring Lee County (named after Confederate General Robert E. Lee), which is 68% White, 23% Black/African American, and where 19% of children are living in poverty. Macon County lags behind the state on several health metrics, including availability of healthcare providers, preventable hospital stays, and premature death. Life expectancy in Macon County is 73.2 years (compared to 78.2 years in Lee County).(5) Macon County is ranked 59 among 67 counties in Alabama in terms of estimated length of life. In last place is Lowndes County (71.2 years), another predominantly Black/African American rural county in the state.(5)

To learn about residents’ views of the health issues facing Macon County, we conducted the Macon Lives Healthier Study. We began this work by creating a Community Advisory Board including residents, city representatives, community leaders, healthcare providers, and affiliates of Tuskegee University, which provided feedback on the objectives of our research, the questions we were asking, and ethical considerations. We sent recruitment letters to randomly selected mailing addresses in Macon County until we reached our goal of enrolling at least 200 participants. We managed to recruit a total of 205 people between October 2020 and December 2021; 164 were Black/African American (83%), and 31 were White (16%). Participants completed a self-report survey and were also asked several open-ended questions.

When queried about what they felt was “the greatest health issue in Macon County,” more than half (57.4%) of participants reported a structural or social issue, rather than a health condition (e.g., diabetes/obesity, high blood pressure, COVID) or individual-level attribute (e.g., health knowledge, diet). The most reported issue was health care access, including the lack of a hospital, followed by deficiencies in the service environment. For example, one participant stated:

We almost live in a desert in Macon County. We have two groceries stores but they do not have good prices for the pay that most people get who live in Tuskegee. Most people in Tuskegee are elderly or on public assistance. I try to take as many elderly people to Auburn [in Lee County] or Montgomery to get groceries because what it costs in Tuskegee to buy groceries is twice as much as in Auburn or Montgomery.

Relatedly, when participants were asked about “barriers to better health” in their community, additional themes that emerged included those around poverty, and the lack of job opportunities. For example, one participant said:

Not a lot of job positions for people to have. Macon County is pretty big but most people drive to Auburn or Montgomery. For individuals that [are] very serious or want to make a certain amount they most likely go to surrounding areas outside of Macon County for work.

Although none of the participants explicitly mentioned racism as a health issue, the concerns that they reported are traceable to historical as well as contemporary forces and racist policies that have led to structural disadvantages that Black/African American rural communities face.(4) Moreover, when specifically surveyed about their own experiences of racism, many Black/African American participants reported experiencing dehumanizing experiences of being treated with less courtesy (68%) or being perceived as less smart (67%). Participants also reported experiencing racial discrimination in specific domains. Most frequently reported were experiences of racial discrimination in getting service at a store or restaurant (64%), followed by on the streets and in public (60%), and at work (52%).

It is important to highlight that despite the deeply entrenched structural challenges in Macon County, we found the community to be strong. When asked about the “strengths of Macon County,” participants mentioned people’s ties to the community and its rich history.

We look out for each other. We help out our neighbors.

The community is trying to work together to improve situations in the county.

The community works well together and they have good means of communicating with each other. They also do a good job at distributing important information to the community.

The history that citizens learn from living in Macon County or being a part of it is one of the best parts of living in Tuskegee.

During the course of the Macon Lives Healthier Study, we learned that the residents are highly resilient and determined. Some were understandably skeptical of participating in this work, in part because of the atrocity of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, but they were also committed to making their community a healthier place to live. These efforts need to be complemented by greater societal investment in communities that have historically been the target of racism. Realizing health justice for Macon County is a critical public health undertaking and a moral imperative.

---

References

1. Cuerda-Galindo E, Sierra-Valenti X, González-López E, López-Muñoz F. Syphilis and human experimentation from World War II to the present: A historical perspective and reflections on ethics. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed) 2014;105(9):847-853. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.08.003

2. Murray CJL, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas: Investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 2006;3(9):e260.

3. Beale C, Cromartie J. The defining characteristics of regional poverty. Perspectives on Poverty, Policy, and Place. Published online Fall 2004.

4. Miller CE, Vasan RS. The southern rural health and mortality penalty: A review of regional health inequities in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2021;268:113443.

5. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2022. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.countyhealthrankings.org