Tulane undergraduate students win Health Policy Case Competition

A team of three Tulane undergraduate students took the top spot in an annual case competition presented by the Department Health Policy and Management at the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. A total of 37 teams from 15 universities competed.

Teams proposed detailed, actionable policies to address the rallying cry “Defund the Police.” The call for submissions sought ideas that would reallocate some city resources rather than entirely abolishing a police department.

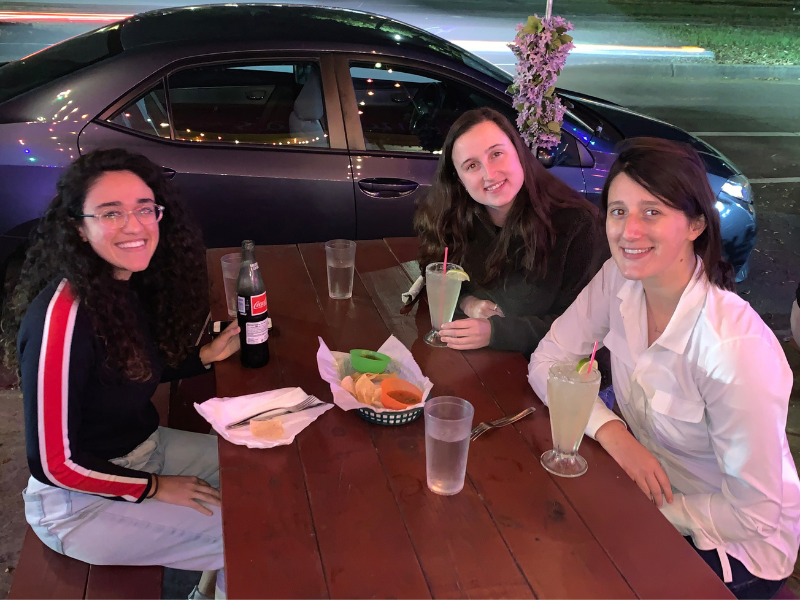

Layla Babahaji, Alexandra Jaouiche, and Melanie Carbery made up the winning team. Babahaji and Jaouiche are both combined degree public health students at Tulane and will be full time in the international health and sustainable development master’s program this fall. Carbery, a public health and economics major, will finish her degree later this year.

The Tulane team’s solution would incorporate crisis intervention counselors (CICs) into the New Orleans Police Department. It was based on a successful program in Eugene, Oregon, called Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets, or CAHOOTS, that began in 1989.

“People in a mental health crisis tend to have extremely negative outcomes with police interactions,” said Jaouiche. CICs are already trained to defuse such crises, she says, especially those where weapons and violence are involved.

While police officers often do get mental health crisis training, it may be only eight hours versus the two to four years of education counselors receive, along with an additional two hundred hours for a specialized CIC certificate.

“Crisis intervention counselors are people that exist and have extensive training [so] it would be a lot easier to do it the other way around,” said Jaouiche. Police departments could hire CICs then give them a shorter version of typical officer training, which would result in an overall cost savings.

It would be a new type of police officer, said Dr. Charles Stoecker, associate professor and director of the competition. “I think what the judges reacted to really positively was that it was a way to get maybe a different kind of applicant for the police force.”

The competition was judged by Keith Lampkin, former chief of staff and policy advisor to then-New Orleans City Councilmember Jason Williams; Katherine Mattes, senior professor of practice, director of the Tulane Law School Criminal Justice Clinic, and co-director of the Women’s Prison Project; Jerome Morgan, co-founder of the Free-Dem Foundations; Antoine Saacks, former NOPD assistant chief of police; and Syrita Steib, founder and executive director of Operation Restoration.

The top three teams also included participants from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Illinois at Chicago. Jaouiche and Babahaji believe their idea stood out because it extremely feasible and implementable. There are no immediate plans to put their ideas into practice in New Orleans

All of the 37 teams participated in a day-long workshop before submitting their proposals. The workshop outlined the steps involved in good policy: identifying the problem, developing potential solutions, gathering evidence, and then judging ideas against established criteria.

“None of them had really encountered policy analysis in that kind of more formal way that we teach in the [master’s] program,” said Stoecker. The competition was a good opportunity for undergraduate students to “try on” health policy as a potential career they might wish to pursue at the master’s level.

Plans are underway for the next competition, but a new prompt has not yet been revealed.